Carbon Quantitative Easing, it may not be a sci-fi fantasy

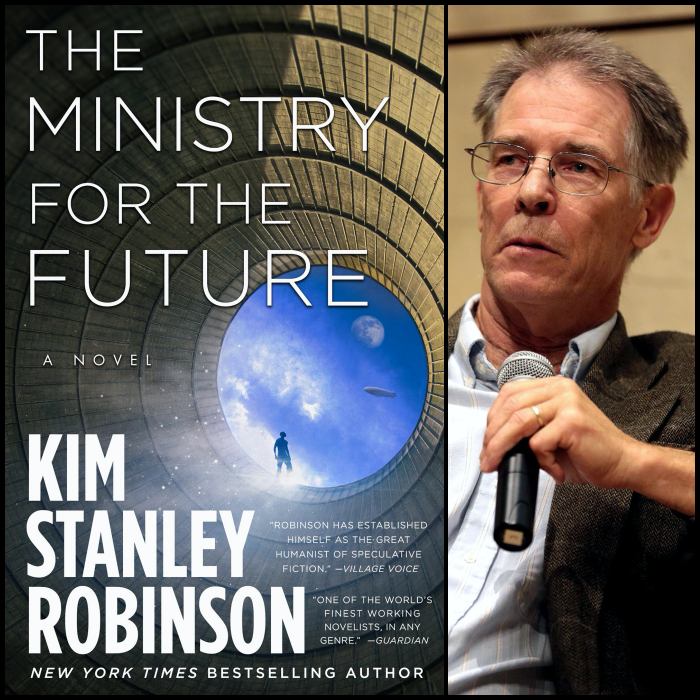

Reducing greenhouse gases, and, in particular, carbon emissions, has been regarded by many as the key to unlocking significant climate repair. To do so, governments around the world have implemented a range of policies, many involving market pressures. Several countries around the world utilize some form of a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system, both of which essentially fine generators for their production of carbon, but science-fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson has proposed a different solution: carbon quantitative easing.

Carbon-quantitative easing would pay people rather than fine them for emitting carbon. Governments would generate new money specifically targeted to pay for rapid decarbonization by encouraging central banks to purchase government bonds, corporate bonds, and other financial assets to increase the broad money supply, or total volume of money held by the public. While it sounds like a far-fetched idea, large central bankers did this during the 2008 recession, spending over $5 trillion dollars buying up longer-term securities from the open market to increase the money supply, encourage lending and investment, and bail themselves out of debt. Carbon quantitative easing would rely on the same rationale but would direct the resulting funds towards addressing climate change.

Under this theory, individuals, corporations, and even sovereign nations would be paid to sequester carbon in the ground for a set period of time in an effort to slow the accumulation of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. An administrative body created by a multinational treaty like the Paris Agreement would certify each carbon-reducing plan and pay out a carbon coin across nations that would distribute the coins to individuals, corporations, and governments who behave in ways that diminish carbon in the environment. The carbon coin would be traded on currency-exchange markets and standardized by central banks that set a floor value and potentially issue long-term bonds for investors as well.

A range of activities like changing infrastructure to encourage mass-transit projects, electric car recharging stations, and de-suburbanization could earn governments, corporations, and individuals carbon coins. Activities like growing forests or transitioning one’s farm to no-till agriculture also count. Robinson believes in the success of this theory due to his faith in government stimulus in times of economic crisis, which has become particularly headline-worthy during the age of COVID-19.

Benefits, Concerns, and Social Considerations

Carbon quantitative easing provides a powerful solution to the ever-intensifying climate crisis. It incentivizes a reduction in carbon emission over time at both the corporate and individual level.

A common call to action among environmental activists revolves around solely blaming large corporations for generating the majority of carbon emissions. While corporations like ExxonMobil and BP contribute the greatest volumes of carbon, individual consumption of goods produced by those companies, like gas and electricity, keeps those corporations afloat.

Neither individuals nor corporations can or should absolve themselves entirely from responsibility for the climate crisis. However, the carbon quantitative easing system would enable individuals to make changes in their consumption habits that would work in tandem with corporate shifts, apportioning responsibility in an equitable manner and rewarding individuals in the process.

Quantitative easing may sound promising, but it also induces both practical and moral concerns. On a practical level, the theory seems to rely on creating money out of thin air. At its inception, carbon quantitative easing would require big central banks to value long term benefit over short term profit. Because the injuries of climate change hit gradually and affect the most vulnerable people in our societies first, bankers are very unlikely to feel the sense of urgency that they did during the 2008 financial crisis. As a result, they are unlikely to decide to move trillions of dollars in investments towards carbon-reducing endeavors that don’t generate immediate capital for them. The initial benefits would be felt most by poor people of color around the world, and that is a demographic that the banking industry has historically severely undervalued, to put it lightly.

On an ethical level, carbon quantitative easing would enable corporations to generate more capital from the climate crisis that they themselves created. Because individuals and businesses could earn carbon coins regardless of their existing wealth, the quantitative easing theory would inevitably put more money in the hands of billionaire corporations that contributed to the climate crisis in the first place. While critics could advocate for the exclusion of corporations from earning any carbon coins, the entire theoretical premise fundamentally requires financial incentives for corporations, for better or for worse.

Carbon quantitative easing is no fantasy solution. It has the potential to revolutionize climate policy and work in conjunction with existing market solutions. The pressing nature of the climate crisis begs for more than one theory of repair. Quantitative easing can and should be added to the arsenal available to nations around the world. Every approach will have drawbacks and ripple effects, and moral implications of the theory are worthy of consideration and attention. But our philosophies for combatting the climate crisis should include a diversity of ideas and theories, and carbon quantitative easing could be one of them.